PART TWO: THE HISTORY OF COUNTRY MUSIC 1970 to 1989

History of country music: 1970 to 1989 explores two decades when UK country fans head to clubs, fields & Wembley to sample country music. The second part of this investigation into country music in the UK takes us into the Wembley Country Festival era. The sound and delivery of country have changed massively, but the importance of performance, songwriting and fandom has not dimmed a watt.

- The Old Grey Whistle Test: A Journey Through Folk, Rock, and a Little Country

- Lee Williams: A Lifetime Dedicated to British Country Music and its Enduring Legacy

- Transatlantic Ties and Timeless Songs

- Alan Cackett: From NME Scribe to Pioneering British Country Music Journalist

- The Golden Decade: Unravelling the Peak Years of Country Music in the UK (1972-1982)

- Good’n’Country: Uniting Country Fans in the Analog Era through Gigs and Festivals

- Breaking Boundaries: Alan Cackett’s Critique of the British Country Music Association and the Insularity of the UK Scene

- Remembering UK Country Legends: Tony Goodacre, Phil Brady, and Frank Yonco

- Line Dance: A Double-Edged Sword for British Country Music Clubs

- Surprising Hits and Misses: American Acts on the UK Charts Revealed

- The Rise and Fall of the Wembley Festival: A Controversial Legacy in British Country Music

- Revitalising British Country Music: Lessons from the 1981 Brighton Festival

UK Country Music 1970-1989

The period from 1970 to 1989 marked a significant era for British country music, highlighted by the emergence of the renowned Wembley Country Festival. However, this period also brought a mixed blessing with the rise of line dancing, posing both opportunities and challenges for the genre’s songwriters and artists. While established UK artists found encouragement and opportunities to record in Nashville through transatlantic record label connections, surprisingly, prominent American country artists struggled to make a substantial impact on the UK Charts during this time.

The Old Grey Whistle Test: A Journey Through Folk, Rock, and a Little Country

In 1971 BBC Two began a sixteen-year run of shows introduced by a theme song from Area Code 615. Stone Fox Chase would signal to serious music fans that The Old Grey Whistle Test was on just before closedown.

Jerry Lee Lewis sang Great Balls of Fire on the second-ever episode on September 28 and again in April – doing a medley of Chantilly Lace/Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin On – and May. Kris Kristofferson offered two songs, including Help Me Make It Through The Night, which he sang as a duet with Rita Coolidge.

Amid the folk and rock that was championed in those days by a bearded host who was prone to whispering his links, over the years, the odd country act popped up: Country Joe MacDonald, Linda Ronstadt, the Eagles and Emmylou Harris, with John Prine making many appearances including a video of Sam Stone early in the show’s run. Towards its end in 1986, Dwight Yoakam appeared a week after a young INXS launched themselves into late-night living rooms and a fortnight after Paul Brady.

In April 1975, Raymond Froggatt played two songs. YouTube holds the clip of Raymond’s performance, introduced by the youthful, bearded, whispering Bob Harris. I’ll Follow You and Dear Friend have a gentle beat, almost soft rock, but a pedal steel player is chiming in underneath Raymond’s assured vocals. The singer announced that he would head to Memphis and Nashville to record an album with Steve Cropper on guitar.

Fun fact, as an aside: Raymond had been managed by Don Arden, father of Sharon Osbourne.

Renowned Birmingham-born rock artist, Raymond Froggatt, embraced a more country-infused sound as his career progressed, leading to his invitation to perform at the esteemed Wembley Festivals. With the support of Mervyn Conn, Froggatt recorded two albums in Nashville, featuring the legendary Jordanaires and Hargus Pig Robbins. His debut album, “Southern Fried Frog,” achieved remarkable sales success. Widely recognized as a key figure in the UK country scene, Froggatt’s musical journey includes collaborations with numerous prominent American artists, including the incomparable Tina Turner, who recorded one of his captivating songs.

Lee Williams: A Lifetime Dedicated to British Country Music and its Enduring Legacy

Raymond turned 80 in November 2021, making him of a similar vintage to Alan Cackett and Lee Williams, who, in the 2010s, served six or seven years as president of the British Country Music Association. He is no longer involved in the BCMA but, as we shall learn, is still keen to promote country music under his own steam.

‘It used to be near Blackpool, and they said would I be interested,’ Lee told me. ‘“Only if we brought it South into London”, I said, which we did. I slowly removed it from the club scene and brought in the bigger names of British country, and Nashville acts, like Steve Wariner. But it became very North v South, and I was the only South!’ he says with a chuckle. Steve came over for the BCMA Awards one year, declining to take a fee so long as the association paid for his ticket. ‘It was brilliant. He had a great time.’

Along with Alan Cackett, Lee is a tremendous primary source, a Zelig figure who was there for country music’s Wembley era, as it may be termed. Like Alan, Lee was at the Slim Whitman gigs in the mid-1950s, which informed his career choice, which took in artist management, promotion and broadcasting.

‘My whole working life has been involved in country music. I ought to write a book as well sometime! I’ve been around a long time, 74 this March, and I’ve always advocated for British country music. I was doing pop music, playing The Who and The Stones, and one day I found Buck Owens, and it changed me overnight.’

Lee had four bands, including the Original Colorado Band, who toured Europe from 1968. They were the house band who backed the American stars when they came to the overseas bases. ‘We toured with Merle Travis and Tompall Glaser. I toured with Johnny Cash in the old days all across Europe.’

Transatlantic Ties and Timeless Songs

Although, he says, ‘there was a healthy club scene in those days, you didn’t get paid much! I started going on the road with John Derek, who used to live in Newbury, where I was. They were doing the Griffin circuit, which had country music eight times a week.’

This circuit included pubs such as the Red Lion in Brentford, one called The Red Cow, and ‘the pinnacle’, the Nashville Rooms in West London. The Hillsiders would come down from Liverpool, joining the scenes North and South of Watford. In 2023, that circuit has fallen away.

‘A lot of the clubs have closed down. In those early days, it attracted young people because those were the boozers in London. You went out at Sunday lunchtime, went in and had a drink, and there was a country band. They enjoyed the music.’

Lee used to manage Pete Sayers, ‘who had loads of TV series for the BBC’, while another client, Diane Solomon, once supported Kenny Rogers. ‘At that time, the musicianship wasn’t as good as it could have been; today, that’s entirely different, and the UK has actually got its own sound, its own style. Everybody sang with a dreadful American accent, but they don’t seem to do that as much. We can hold our heads up high.

‘I did learn a long time ago to separate a country music anorak from a music fan who enjoyed country music. I’m one of those and love soul music and metal sometimes. But if you come down to it, I get the most satisfaction from a good, traditional country song.’

Lee groans when I mention David Allen Coe, whose shows he also put on, quoting a gargantuan loss of earnings. ‘He caused me much grief. He made me lose my hair. It was horrendous! It’s a very sore point for me. I still think he’s an amazing artist!’ He mentions that Buck Owens and Billie Jo Spears ‘got done by an Irish promoter. Billie Jo died from the stress of it.

‘I don’t have the infrastructure or staffing to do all the red tape. You were changing dates, and it didn’t pay enough to have all that headache; I stopped it a long time ago. You have to be a LiveNation with loads of staff, pick up the phone, and sort work permits.’

Dan Seals, meanwhile, was just ahead of the time when he came over. ‘He didn’t make any money. Nobody really knew who he was. We did theatres, but it was never big, big, big. It was a great experience.’

Lee used to have an office in Nashville and would throw a party during CMA Fest. He learned two things: ‘One, there are too many acts around, and two, the CMA seemed to wipe it over so that you couldn’t do it yourself. That’s life.’

Lee got these clients by pressing the flesh in Music City. ‘I’ve been going to Nashville since 1973. I’ve been 30, 40 times.’ The British acts he took over to Nashville ‘did very well at the time.’ In 2023, Lee is hopefully going to the Country Radio Seminar.

‘I was introduced to Steve Young for the first time, who wrote Seven Bridges Road for the Eagles and some Waylon Jennings hits. I had an American act on tour every month for about three years: a great Texas guy called Robert Joe Vandygriff, an excellent club act who came over several times, plus people from Canada. Joe Firth, Paul Webber, Grant Carson Band. In their time, they were popular.

‘That all went well until the mid-eighties. I now know what killed it all: a huge three-day working week. Everybody didn’t have any money. Clubs used to book through an agent, and they got friendly with the acts. They got their number, and when it all got hard, they called the acts directly, which they thought would save them some money. It didn’t, but they thought it did. That killed the scene a lot. People weren’t loyal to the ones building them up.’

In addition, Lee says the club scene got a bit political. You’d have the sheriff running it; all dressed up, and his friends too. Young people would look at that and think, “I ain’t going in with Mum and Dad to see that!” The rockabilly scene was different because the fashion was cool, and the kids loved it. They still do.

‘I just put on a rock’n’roll show, [hosted by] my godson, on Saturday night. He got MS, but he’s got a great style and such a following!’ That show is on CMR Nashville, a station featuring a worldwide network of presenters under a country umbrella. ‘I try to keep out of that competition thing,’ Lee says of the challengers to his throne.

Launched in the 1990s on satellite radio under a different name, the station evolved into its current name. It broadcasts a weekday schedule of eight hours of radio repeated twice and a 12-hour weekend schedule repeated once. It is a sort of BBC World Service for country music.

A British Trailblazer in Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry: Pete Sayers, born on November 6, 1942, in Bath, England, holds a unique distinction as the only British performer to become a regular guest on Nashville’s iconic Grand Ole Opry. During his teenage years, Sayers formed the Bluegrass Cut-Ups, which is believed to be one of Britain’s earliest bluegrass bands.

In Music City Nashville, Sayers found his place as an Opry warm-up artist, a role he embraced until 1969. Not only did he entertain the Opry audience before shows, but he also made frequent appearances on the revered programme itself. Furthermore, Sayers ventured into television hosting, presenting three notable BBC series: “Pete Sayers Entertains,” “Electric Music Show,” and “Pete Sayers Sings Country.”

Beyond his performances, Sayers made significant contributions to the country music scene in England. He established the Grand Ole Opry (England), organizing shows that captured the essence of the legendary Nashville institution. In 1973, Sayers released his debut solo album, “Bye Bye Tennessee,” on Pye Nashville International, showcasing his musical prowess and further cementing his place in the country music realm.

Alan Cackett: From Kent Messenger Scribe to Pioneering British Country Music Journalist

In the 1970s, Alan was working in the production team at the Kent Messenger, eventually rising to Production Manager by the early 1990s. In the previous decade, he was caught up in trade union disputes and worked long hours, passing the picket lines to keep the newspaper running. He also wrote a weekly country music column for the paper to go with the one he wrote for Country Music People. He also contributed at various times to Sounds and Record Mirror, a couple of pop music publications of the 1960’s and 1970’s writing about country music.

‘We published a free newspaper which covered the whole of Kent; half a million copies were printed. The editor asked me if I was interested in reviewing pop music for them. They got all the new singles before they came out. Of course, I was interested; I grew up on pop, so I wrote pop music reviews for nearly 20 years, from 1974 to about 1995.

‘I walked into a country music club one Saturday night because there was an act on that I particularly liked. This guy walked up to me dressed in all the cowboy regalia, which I never wore. He tapped me on the shoulder and said: “You’re Alan Cackett, aren’t you? You don’t know shit about country music.”

‘Somebody standing next to him knew me. He turned around and said, “If you live to be a thousand years, you wouldn’t know anything near as much as this guy does about country music.” So the first guy says, “But you write pop music reviews!” I said: “That’s what enables me to write country music reviews because I know where I’m coming from!”’

Alan still heads over to Nashville to attend Tin Pan South, a festival for songwriters, which in 2023 happens in nine venues across the last weekend of March. As with the Bluebird Café event at Country2Country, festivalgoers pay an entrance fee (here, $15-$20) for showcases and events. Big names at the 2022 festival included songwriters from every vintage: from Bill Anderson, Buddy Cannon, Bob DiPiero, Victoria Banks, Lee Thomas Miller, Jon Nite, Chris DeStefano and Rodney Clawson; to hot A-Listers of today like Corey Crowder, Jimmy Robbins, Randy Montana, Caitlyn Smith, Ben Johnson, Ashley Gorley, Liz Rose, Eric Paslay and Hailey Whitters.

Alan was, he says, ‘the first person in the UK to write about Don Schlitz. I got a copy of The Gambler, put out on a small independent label, sent by a PR guy, a couple of years before Kenny Rogers got hold of the song.’ I ask if Alan has ever been tempted to write a country song of his own.

‘I had a go, but it was a dismal failure. I can’t sing to save my life and have no sense of rhythm. I can’t dance! I can’t read music, so I don’t enjoy reviewing instrumental albums because it’s the words, the stories and the vocalist that move me. I loved to sit down and hear the writer sing a song he wrote that was a big hit for somebody else, explaining how the song came about. Even if they can’t particularly sing well, they put a personal touch to their interpretation.’

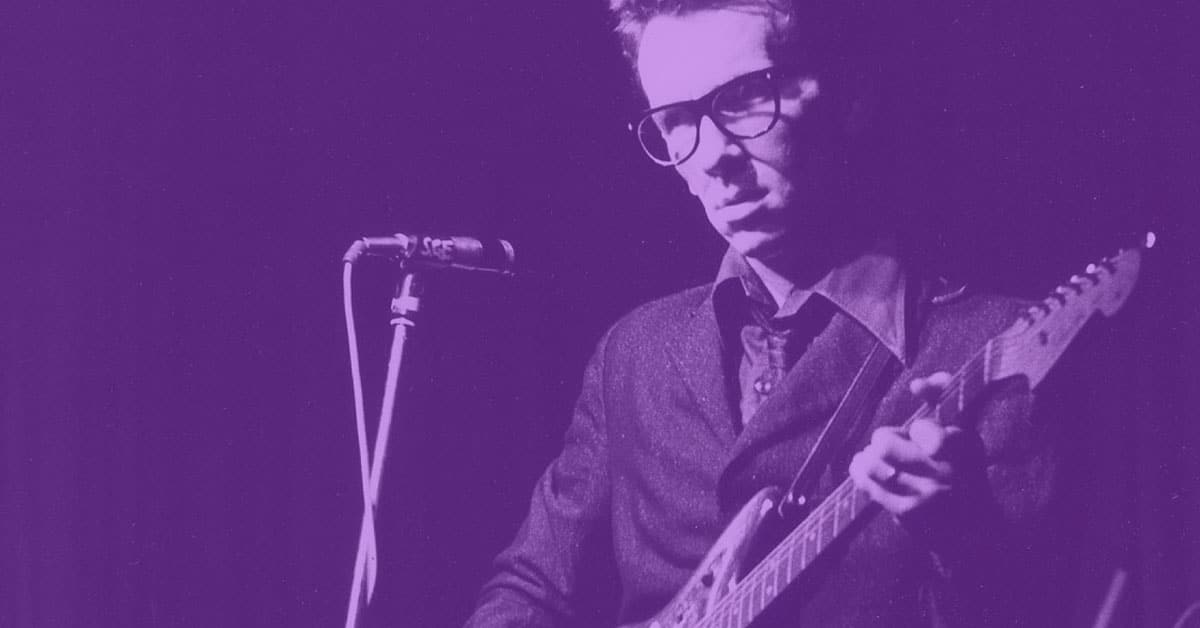

Elvis Costello Explores Country Roots in “Almost Blue” Album

“Almost Blue” stands as the sixth studio album by renowned English singer-songwriter Elvis Costello, marking his fifth collaboration with the talented lineup of the Attractions, including keyboardist Steve Nieve, bassist Bruce Thomas, and drummer Pete Thomas (no relation). Recorded in May 1981 in Nashville, Tennessee, the album was released in October of the same year. Departing from Costello’s previous works, “Almost Blue” takes the form of a covers album, entirely composed of country music songs.

This captivating collection opens with a thrash punk rendition of a Hank Williams song, offering a delightful surprise for listeners. True to Costello’s style, his interpretations of country classics exude a heightened sense of turmoil, as evident in his rendition of “How Much I’ve Lied” when compared to the original by Gram Parsons. Backed by slick production, courtesy of Billy Sherril (who also penned “Too Far Gone”), and thoughtful packaging, the album offers both a personal introduction to the genre and an exploration of Costello’s musical influences, showcasing well-known figures like Parsons, Haggard, and Mathis, alongside lesser-known songwriters.

The Golden Decade: Unraveling the Peak Years of Country Music in the UK (1972-1982)

As a chronicler of the country movement in the UK, he can conclude that the era where country music in the UK was most popular was ‘between 1972 and 1982. The Val Doonican Show was on BBC TV on Saturday nights. He would have Roger Miller, John Denver, and Jerry Reed playing to a viewing figure of 22 million people. They weren’t country music fans! The Cilla Black Show too.’

At the time, Faron Young and Billie Jo Spears were getting high up into the pop charts, the former with It’s Four in the Morning (number three in 1972) and the latter with two top ten hits: Blanket on the Ground (number six in 1975) and What I’ve Got In Mind (number four in 1976).

These were the peak years of the rock era, the age of the LP documented by David Hepworth in his essential study A Fabulous Creation. Many rock performers ‘went country’. Bob Dylan called his 1969 album Nashville Skyline, which opened with a new version of his song Girl from the North Country with his friend Johnny Cash. Big hit song Lay Lady Lay was initially submitted for the movie Midnight Cowboy, having been written for Barbra Streisand. Nashville session musicians Charlie Daniels and Charlie McCoy were drafted in by Dylan, as was pedal steel guitarist Pete Drake, who can be heard on Stand By Your Man. Drake was celebrated with a Country Music Hall of Fame induction in 2022.

For his 1970 album Beaucoups of Blues, Ringo Starr also employed Nashville’s session musicians, including Daniels, McCoy and Jerry Reed, and both The Jordanaires and DJ Fontana, Elvis Presley’s backing vocalists and drummer, respectively. Oddly, considering The Beatles had only released their last album months beforehand, UK fans didn’t buy his album. Ringo had a country pedigree: he had sung a cover of the Buck Owens tune Act Naturally and had written the country-tinged pair Don’t Pass Me By and What Goes On. Ringo would have to wait for 1971’s It Don’t Come Easy to have a hit, though he did have two Hot 100 number ones with the pop songs You’re Sixteen and Photograph.

The Transatlantic link between record label offices in the UK and the USA must have helped prominent artists head to the States. Dusty Springfield went to Memphis, while Elvis Costello recorded his album Almost Blue in Nashville as he looked towards country music and took his fans with him. Elton John, of course, wrote the music to Bernie Taupin’s tales of brown-dirt cowboys and tiny dancing seamstresses. Inspired by Alan Cackett’s beloved Gram Parsons, the Rolling Stones headed to Muscle Shoals Studios in Alabama to record their epochal Sticky Fingers LP, which began with Brown Sugar and included Wild Horses.

Alan says, ‘All these things are isolated, ‘it needed something to pull it all together. That never really happened. You didn’t have a way of connecting people up 40 or 50 years ago.

‘I often thought I was one of a handful listening to the cosmic contemporary country music. In a way, that’s what drove me to write about it. It’s only in the last fifteen years, because of social media, that I’ve suddenly found that many people my age were listening to the same stuff as I was all those years ago.’

Good’n’Country: Uniting Country Fans in the Analog Era through Gigs and Festivals

In the analogue era, country fans had to be in the same room as each other or had to subscribe to the same magazines. Alan promoted gigs where such people could convene, not under his name but with the brand name Good’n’Country, with the logo physically branded as if it were cattle. Amusingly, he relied on trains and friends giving him lifts because he didn’t have a driver’s licence. Among the American acts he booked were Gene Watson and George Hamilton IV.

Alan set up the Good’n’Country Festival, held at a Kentish farm, but it became a nightmare due to all the paperwork and crowd management. A crowd of five thousand enjoyed the 1988 festival, with 18 acts, and then ten thousand showed up for 1989. Bad weather scuppered the number of walk-ups for the 1990 festival, and Alan focussed on indoor gigs in the 1990s.

‘When I used to put country music on, it was in an art college in Maidstone,’ he tells me. ‘I didn’t attract people from there; I attracted people from the general public. I knew how to get an editorial in the newspaper, so without that, I wouldn’t have succeeded in promoting the music. They attracted 600 people to them: a local Kentish country band would open, then a cabaret act in the middle which would be a solo artist who wrote all of his material or a mix of that and covers.

‘Then I’d have a band from outside the area – The Hillsiders from Liverpool, for example – who would come down as a one-off because I’d got 600 people. I could pay them good money to make it worth their while with the proviso that they didn’t appear anywhere else in Kent. I knew that I could sell it out. Every single one of them was a nail-biting thing until the evening of the show because that’s what promoting music is all about. It’s a gamble.’

‘I love Alan,’ Lee Williams tells me of his longtime pal. ‘I used to supply most of his acts for the Hop Farm festivals. Tompall Glaser was down there, onstage. He looked like he was in a shower singing, an amazing sight!’

‘Whenever I put a show on,’ Alan Cackett continues, ‘I always had the cash available beforehand to pay the artists. If nobody came through the door, the artists got paid for whatever happened. My integrity remained sky-high. For the festival, I put aside £40,000. We were selling the tickets from January, and the festival was in June or July.’

If a fan wanted to meet the artist or take home a souvenir, there was a merch tent: ‘We made sure that when they came off stage, they signed autographs.’ Alan took no commission for the merch sales for acts like Frank Jennings Syndicate and The Duffy Brothers.

Frank Jennings Syndicate: From Grand Ole Opry to London Palladium – A Journey with Country Legends

The renowned Frank Jennings Syndicate (FJS) made a notable impact on both sides of the Atlantic, gracing esteemed stages such as the iconic “Grand Ole Opry” and the prestigious “London Palladium.” Their exceptional talent led them to collaborate with country music greats, including Tammy Wynette, George Jones, Faron Young, and numerous others.

Emerging in the 1970s, FJS rose to prominence during a thriving period for country music in the UK. Their remarkable journey reached new heights when they claimed victory on the popular TV talent show “Opportunity Knocks.” This milestone led them to record for EMI at the legendary Abbey Road studios in London and Nashville, the heartland of country music.

Born in 1944 in London to Irish immigrant parents, Frank Jennings stood as a distinguished country singer, leaving a lasting legacy within the genre.

Breaking Boundaries: Alan Cackett’s Critique of the British Country Music Association and the Insularity of the UK Scene

The British Country Music Association rebooted itself in the late 2010s under the leadership of BJ Thomas, father of guitarist Luke. For all the championing it does of the UK scene, the BCMA often gets criticism for being insular in 2023. Alan made that point in 1980, calling it a fan-oriented organisation that fulfils a necessary need, yet its very setup hinders the scene’s progress.

Today he cannot remember why the BCMA Awards 1980 were labelled ‘a complete farce’. At the time, he wrote that the organisation was ‘completely out of touch with what is happening, and the failure to direct the development of country music in Britain makes the organisation ineffective.’

‘I’ve always stood outside the UK scene,’ Alan says in 2023. ‘It’s very insular and has been held back over the decades when they haven’t welcomed younger people to participate. They’ve not embraced changes in the music until it’s too late.’

In his role as writer and promoter, Alan was an original BCMA committee member. He helped assemble a Yearbook, a country Yellow Pages with all the acts, all the clubs and contact details. ‘Many British acts in the seventies had record deals, but it didn’t mean they had success.

‘They were treated like third-division pop acts: sign them and see what happens. The music industry was still very much geared to the charts, and getting a British country act into the singles charts was impossible. Frank Jennings Syndicate got to about number 33 on the album charts. They did three albums for EMI. Their producer, a staff producer, was into country music.’

The band had won Opportunity Knocks and put out singles like A Good Love is Like A Good Song. There’s a clip of them performing on American TV: complete with fiddle, pedal steel and organ in the band; Frank has very British teeth and the same facial hair as Kenny Rogers. The song itself is none more mid-seventies with the same gentle beat and inoffensive tenor as one of Kenny’s hits.

Remembering UK Country Legends: Tony Goodacre, Phil Brady, and Frank Yonco

There were plenty of UK acts on the circuit: Stu Stevens, Phil Brady & The Ranchers and The Kentuckians (from Liverpool); The Country Cousins and Jonny Young Four (from Kent); Lincoln Park Inn and Country Fever (from London); and Frank Yonco, who was based up in Manchester. Frank knew how to entertain crowds and was praised by Alan Cackett for ‘treating the public with respect’. One of Frank’s albums was called If You Don’t Like Hank Williams, while his memoir was named Jack Daniels If You Please.

Tony Goodacre was born in Leeds in 1938, starting as a skiffle musician during his period of national service, where he became familiar with US country recordings from the Air Force. Upon demobilisation, Tony played music in the evenings while earning money in sales. 1973 was a big one for him, as he won the Record Mirror Award and headed over to Nashville; 1974 saw him play 354 gigs across Yorkshire’s working men’s clubs, the hardest-working man in UK country. Three years later, he was ready for the Grand Ole Opry.

Tony was the BCMA Best Male award-winner in 1981, 1983 and 1984 and would play a Dutch country festival, The Floralia. He moved into management, steering the career of his band member Sarah Jory, and he also found time to set up Sylvantone Records with his wife, Sylvia. Tony then played at the Tamworth festival in Australia, another market he did well in, and was part of a tribute show at the Palladium in London to honour Jim Reeves. He was good friends with George Hamilton IV, for whom he organised a month-long tour in 2006 with no days off! Britain’s Mr Country Music died in June 2022.

Phil Brady died in March 2021, an event marked in the Liverpool Echo. Born in the Dingle region of the city, the same part as Ringo Starr, Brady had become hooked on country via AFN and would own records brought back from his friend’s dad, who worked on the famous Cunard Line. David Bedford told Phil’s story in a book called The Country of Liverpool, ‘The Nashville of the North’ as it was known. Along with Phil was the pair Hank Walters, who played with his band The Dusty Road Ramblers, and Kenny Johnson, the frontman of the Hillsiders mentioned above, who presented a country show on BBC Radio Merseyside.

On David’s website is a poster advertising Buck Owens’ ‘exclusive Liverpool appearance’ at a gig put on by Mervyn Conn; Phil Brady is one of the support acts along with his band The Ranchers. He was also on the bill at the Palladium on the undercard for a Hank Snow gig put on by Opry Magazine. Tickets were priced at 10 shillings up to £8 for a box.

It was amazing that Phil could get down from their Liverpool base, judging by a paragraph in the Echo obituary which outlined the demand for them. The Ranchers ‘became resident at the Blue Angel on Monday nights, the Chequers Club on Tuesdays, the Four Winds on Wednesdays and the Marine Club on Thursdays.’ A single called An American Sailor at the Cavern came out in 1965, and it is a perfect mix of Scouse balladry – a place for Me by the River Mer-see’, namechecks for the four famous ‘fine young fellas’ and Cilla Black – and a three-chord Nashville arrangement with dustings of the fiddle.

Line Dance: A Double-Edged Sword for British Country Music Clubs

For Alan Cackett, British country music clubs were a problem. At his own events, he says: ‘I had space at the side of the stage where people could line dance. I’ve never been in favour of it. To my mind, line dance held back country music, and it saved it at the same time. It was a double-edged sword. It killed off the people who went to the clubs to listen because everything had to be done to beats per minute, so the acts did their act solely for the line dancers. The creativity went out of it.

‘The fans that went to the British country music clubs would not allow the acts to sing their own songs. I encouraged them to do their songs when they did my gigs. They went down a storm, but they weren’t playing to the same crowd that dressed up as cowboys. They were playing to an audience that wasn’t necessarily into country, but they’d come to the local theatre to do a show.

‘I’ve got really exceptional albums, and nobody’s heard them. Joe Brown’s A Picture of You was a pop hit [number two in 1962]; it’s a country song. At the time, it could have been recorded by somebody like Buck Owens!’

Alan wrote a piece in 1980 where he opined that ‘it appears to be a case of quantity above quality today. There are still only around a dozen groups which could rightly be termed top-class. I have no idea exactly how many country bands are currently working in Britain. Judging by the listings in the BCMA Yearbook, I would guess that there must be four times the number that was around in 1970.’

Surprising Hits and Misses: American Country Acts impact on the UK Charts Revealed

Let’s take a break from the chronicling of UK acts and return to the performance of American acts on the UK charts, some of which might surprise you.

How many hits, for instance, did Johnny Cash have over here? You would think quite a few, but he only had six: Bob Dylan’s It Ain’t Me Babe, the satire A Boy Named Sue, a little-heard poser called What Is Truth, the mellow A Thing Called Love and One Piece At A Time. He had his posthumous hit with Hurt, which snuck into the Top 40 at number 39 and propelled the sales of America IV: The Man Comes Around.

Alabama and George Strait, the key money-spinners in 1980s Nashville, never charted on the Top 40 over here. Nor did Alan Jackson or Randy Travis, although Forever and Ever Amen did get a release in May 1988 but stalled at 55. Dolly Parton, whose manager got her in front of pop crowds and onto the big screen, had a total of two UK chart entries – two. – both top 10s and, in fact, both number 7 hits: Jolene in 1976 and Islands In The Stream in 1983. The song 9 to 5 stopped at 47, but it rose to number one in the US. Handily, though, I Will Always Love You was the 1992 UK Christmas number one for Whitney Houston. Dolly famously turned down Colonel Tom Parker, who wanted Elvis to sing it, as well as some of the copyright.

This means that Charlie Rich – with The Most Beautiful Girl (number 2 in 1974), Behind Closed Doors (number 16, riding the previous single’s coattails), and We Love Each Other (number 37 in 1975) – was a more extensive UK hitmaker than Dolly, the performer. Before her pop career, Olivia Newton-John took her country hits Banks Of The Ohio (number 6 in 1971) and her version of Take Me Home Country Roads (number 15 in 1973) into the UK charts, while that song’s writer John Denver was a one-hit wonder thanks to his Transatlantic chart-topper Annie’s Song in 1974. His duet with Placido Domingo, the gorgeous Perhaps Love, stalled at 46 in December 1981.

Merle Haggard never charted in the UK, nor did Waylon Jennings or George Jones. Think again if you think Willie Nelson must have been popular as a chart act. Only his Julio Iglesias duet charted (number 17 in 1984), and Always On My Mind fell short (number 49 in 1982). His Legend collection from 2008 charted in the UK album charts.

Mary Chapin Carpenter crept into the Top 40 twice in 1995: a Shawn Colvin duet called One Cool Remove (number 40 in January) and her track Shut Up and Kiss Me (number 35 in July). In 1993, He Thinks He’ll Keep Her hit number 71. Tammy Wynette, of course, told listeners to stand by their man, and thousands took the song to number one; a few weeks later, in the summer of 1975, D-I-V-O-R-C-E hit number 12, and it inspired Billy Connolly to lampoon it in a song that shot to number one too. Billy, of course, was a folkie in Scottish clubs that often let in country performers. Four years later, Charlie Daniels Band took the story of duelling fiddlers to number 14; I remember Gareth Thomas danced on ice to it on primetime ITV.

Tammy would return to the charts in the same era when Dusty Springfield worked with the Pet Shop Boys. Pranksters, The KLF convinced Tammy to sing about ‘driving ice cream vans’ on the sui generis Justified and Ancient, which was kept off the top in December 1991 by the reissued Bohemian Rhapsody. It put Tammy in the same top ten as Diana Ross, Guns N Roses, Michael Jackson and George Michael & Elton John, whose live version of the latter’s country-tinged tune Don’t Let The Sun Go Down On Me was also on the Woolworths’ CD racks to entice people to spend record tokens on a new version of an old song. Perhaps Garth Brooks’ Ropin’ The Wind was over on the LP racks.

Olivia Newton-John: From British Roots to Australian Upbringing, Conquering American Country Music

Born in Britain and raised in Australia, Olivia Newton-John emerged as one of the most revered country singers who not only achieved tremendous success on the American Billboard but also captured the hearts of American country music enthusiasts.

Her fortunes took a significant turn with the release of “Let Me Be There” in 1973, propelling her to the top 10 of the American Pop (No. 6), Country (No. 7), and AC charts. The title track from her U.S. album debut, “Let Me Be There,” not only garnered commercial success but also earned her prestigious accolades, including recognition as the Most Promising Female Vocalist by the Academy of Country Music and a Grammy Award for Best Country Vocalist.

With an impressive career spanning over 50 million album sales, Olivia Newton-John boasts a remarkable collection of three additional Grammy wins, along with numerous honours from the Country Music, American Music, and People’s Choice Awards. Her journey from British origins to an Australian upbringing served as the foundation for her extraordinary musical achievements, ultimately solidifying her place as a beloved figure in American country music.

The Rise and Fall of the Wembley Festival: A Controversial Legacy in British Country Music

Writing in a 2022 issue of Country Music People, David Allan considered the British Country Music Festival itself, asking if it would be a winning format of the future: a country music event that quite deliberately isn’t all country.’ He called the idea ‘bold’ and wasn’t entirely sure of the festival’s USP. Then again, David concludes, a little bit of promotion ‘spurred on the inaugural Wembley Festival’.

It was that festival that was the C2C of its day. Mervyn Conn was the impresario who set up what he named the International Festival of Country and Western Music, designing a poster with twin guitars with their backs painted as a Union flag and a Stars-and-Stripes one.

The festival venue was still called the Empire Pool rather than Wembley Arena. Radio presenter Stan Laundon has provided a valuable service on his website by listing the full line-ups of this festival, which began in 1969. Head to stanlaundon.com/wembley.html, especially for a nostalgia hit if you have been to any of the festivals. Hank Snow, Jeannie Seely, Freddy Fender, Skeeter Davis and Don Williams were regulars.

Conn had served his apprenticeship for Joan and Jackie Collins’ father, Joe, from where he went on to promote three Johnny Cash tours of the UK and shows by Tammy Wynette; Tammy and George would, according to the title of the show he put on, be Together Again. Conn also promoted musicals such as Annie, and he brought The Byrds to the UK on the strength of a performance in Los Angeles.

The big names in the first show on April 5, 1969, were Bill Anderson, Loretta Lynn, George Hamilton IV and Conway Twitty. Throughout the 1970s, many Music City stars flew over: Waylon Jennings and Jessi Colter in 1971, Anne Murray in 1972, Jeannie C Riley in 1973, Johnny Rodriguez in 1974, and Wanda Jackson in 1975 and 1976. Last year they brought Connie Smith, Dolly Parton and Carl Perkins, which encouraged Crystal Gayle and Larry Gatlin to join the fun in 1977. A programme from the 1978 festival shows that the jamboree would gallop to Sweden, Finland, Norway and the Netherlands.

Alan Cackett was present at all Wembley festivals, including three for which reviews can be found on his website. Tammy Wynette, reeling from her divorce, headlined the 1976 show. Between Wanda Jackson and Don Williams came the Ulsterwoman Philomena Begley, whom today is still kicking at 80 and enjoys being known as the Queen of Country. She is the aunt of Voice UK winner Andrea Begley.

On a Monday night in March 1978, the third night of the festival, Alan documented an evening headlined by Merle Haggard, featuring A-Listers Dottie West and Kenny Rogers (‘a good, consummate performer’). Merle, by contrast, barely acknowledged the audience, with Alan wishing he would be a person, not a well-oiled jukebox’.

Tompall Glaser was there too, with his ‘deafening’ band helping him to deliver ‘an appalling’ T For Texas. After the interval, there was a retinue of girls ‘aged between four and nine’ going under the name The Mervyn Conn Wimbledon Dancers. Mervyn, the man behind the festival, was visibly annoyed at an error with the backing track.

There were also two musical performances from competition winners: West Virginia, a group from Liverpool, and The Duffy Brothers represented solo acts or duos. Respectively they covered Rachel by Rodney Crowell and the standard Orange Blossom Special. The show also featured a man chosen to represent the UK at what is now CMA Fest which was then the International Fan Fair. Raymond Froggatt mentioned earlier that he had been ‘the centre of controversy’.

‘He was the wrong pick,’ Alan says today. ‘In his early days of changing over to country, the fans who were very traditionally slanted still saw him as a pop singer from the sixties. They felt that he shouldn’t go to Nashville to represent the country scene.’

Alan was equally disappointed with the festival and its many ‘below par’ British acts when he attended the opening Saturday night show in 1979, which was graced with A-Listers Marty Robbins and headliner Billie Jo Spears. ‘It is still down to a few thousand keen enthusiasts keeping the dinosaur alive and kicking.

‘The Saturday evening show was littered with acts that had transitioned from pubs and village halls to the Wembley Arena without the standing or the talent to back up their inclusion. To appear at Wembley is an honour, and I feel that more care should be taken when considering whom to include on the bill.’

Poor Nancy Peppers and Al Doherty were deemed unworthy of a “place on the bill”. Philomena Begley and Warrington band Poacher (who won New Faces in 1977) were more impressive, but the Duffy Brothers suffered from a microphone issue. Worse, their acoustic act was unsuitable for Wembley Arena’s ‘impersonal environment’. Alan notes that ‘the main appeal of Wembley is, of course, nostalgia’, and one-act was praised for taking ‘guts not to take the easy way out and give the audience the only thing they seem to understand—standards’.

By 1981, Johnny Cash and Waylon Jennings deigned to appear, with Tammy Wynette naturally returning too. (One wonders if the International Festival of Tammy was a moniker for the event.) Across three days in 1982, songwriters like Guy Clark and Kris Kristofferson were the big names, and for a second year in a row, Jerry Lee Lewis was there too, along with Roy Orbison. Slim Whitman and Glen Campbell made their only Wembley festival appearances in 1984, and in 1985 acts were as varied as The Osmonds, the Bellamy Brothers, Brenda Lee and Rita Coolidge. Country music has always been a broad church, after all.

Johnny returned with June and Carlene Carter in tow in 1986, where The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and Jerry Jeff Walker debuted. Alan Cackett’s foe David Allan Coe played at the 1987 festival, as did Little Jimmy Dickens, dobro maestro Jerry Douglas, Patty Loveless and, for the first time, Tanya Tucker. Willie Nelson came to Wembley in 1988, as did Elvis’ backing group, The Jordanaires and, oddly, Daniel O’Donnell.

Willie’s friend Ray Benson brought his crew Asleep At The Wheel to play as part of a great line-up in 1989 that included Buck Owens and Townes van Zandt. Performing, too, were Keith Whitley and Lorrie Morgan, who were married at the time; Keith would die weeks later, leaving Lorrie a widow. Willie and the Wheel would return in 1990, a festival where Mary Chapin Carpenter debuted. The following year was the final Wembley festival.

AllMusic.com writes it ended because of sponsorship issues and ‘an unfashionable image as Conn did not feel comfortable switching to New Country performers’. Once again, Tammy Wynette headlined while there was also an appearance from Crystal Gayle and a tribute to Patsy Cline.

A shadow hangs over the reputation of Mervyn Conn. In 2016 he was convicted on two counts of sexual abuse and jailed for 15 years.

Before he was jailed, Conn brought back the festival in 2012 and was profiled in the Guardian. We learn that he was awarded the Freedom of Nashville. He was called ‘irrepressibly energetic’, which is why he avoided retirement. Now in his eighties, his first chance to appeal his sentence is in 2023, but regardless of whether or not he is in prison for the rest of his life, he is now on the sex offenders’ register.

British country artist Jon Derek and renowned guitarist Albert Lee discussed forming a new band with a slightly more progressive slant. Pinching the name of this band from a recent Ricky Nelson album release, Country Fever.

They received a ‘Certificate of Merit’ in February 1970 for their outstanding contributions to British country music from the ‘CMA of Great Britain’.

In March 1970, Jon made his first appearance at stalwart promoter, Mervyn Conn’s ‘International Festival of Country Music’ known more commonly as the ‘Wembley Country Music Festivals’. Together with Country Fever, they appeared in their own right and on the same show also backed American artists Don Gibson (Sea Of Heartbreak), and Charlie Walker (Pick Me Up On Your Way Down).

Revitalising British Country Music: Lessons from the Brighton Festivals

Conn was not the only promoter trying to make money from country fans. Alan Cackett, who was one of them, had written that if country music in the UK was a ‘dinosaur’ in 1979, by 1981 in Brighton, it seemed to lie extinct.

‘British country music should be thriving,’ he wrote in Country Music People about the fourth Brighton festival of 1981, but ‘it virtually curled up on the seafront and all but died right in front of me.’ Alan was left wondering if there was a British scene at all, calling it a myth…There is not much future for the genre, which he thought was more about putting on a costume than listening to music.

He knew who was responsible: ‘frustrated Hopalong Cassidys, living out their suburban hillbilly fantasies’ who didn’t support UK acts. As he mentioned in his Wembley festival review, those performers were used to pubs and clubs and couldn’t scale up to bigger venues. As for Miki and Griff, he wrote that the duo ‘epitomise all that’s wrong with British country, a musical form stuck way back in the past. This ageing pair are as smooth as treacle. After a while, all the saccharine proved too much for me, so I retreated to the bar, but not before I saw them going through all the inevitable oldies like A Little Bitty Tear, For The Good Times and the “National Anthem” Crystal Chandeliers.’

Alan enjoyed the MOR country of Sounds Country, but Kevin Henderson’s band suffered from sound issues. Other acts included Front Page, with singer Carey Duncan, who impressed Alan far more than Brian Golby’s bluegrass and John Hutch (‘his choice of material was uninspiring’). Knowing his Liverpool readership, he applauded the variety of Hank Walters and the Dusty Road Ramblers (‘Cajun to Western Swing’).

Astoundingly, bearing in mind this was 1981, Frank Ifield was the headliner, covering songs made famous by Eddie Rabbitt and Ronnie Milsap. Ifield was backed by the British band Barbary Coast who also performed their own set. The Wembley festival would pootle on for another decade, but, as you might have seen above, the biggest chart acts of the time, Alabama and George Strait, were never convinced to play to UK fans.

Further Reading

Further Reading for Part Two The Origins of Country Music

English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians by Cecil Sharp

Folk-Songs of the Southern United States by Josiah H Combs

John Jacob Niles’ essay in The Great Smokies and the Blue Ridge, edited by Roderick Peattie

A DEEPER DIVE INTO UK COUNTRY & AMERICANA

We are developing a history of UK country music and the effect the British Isles have had on American country music.

Click the link to our article The Origins of Country Music, the first in a four-part series exploring country music in the UK. Delve into our history and influence on the birth of country music.

To access our History of Country Music articles which is the second instalment in our series on country music in the UK. Immerse yourself in the captivating narrative of our country's rich country musical heritage.

UK Country Music 1930s to 1960s

TBCMF's New Country & Americana Playlist is updated weekly. Our spotify playlist shares the latest realease from UK artists.

Welcome to the UK Country and Americana Chart - The most listened to songs of 2023/24 powered by The British Country Music Festival.

Frequently Asked Questions, advice on tickets, timings, travel, accessibility accommodation, festival details for The British Country Music Festival

Click the link to learn more About The British Country Music Festival, explore our history, our place in the UK country music scene, and our future ambitions.

Recent Comments